Edited by my beloved friend K.L

I do not have any gift for drawing.

Usually, when I say this, my friends (lovely and caring as they are) would go straight to boost my self-confidence, being convinced that the impostor syndrome is speaking for me.

As I am an illustrator, saying that I do not have any gift for drawing may sound absurd. Some people may even think that it was false modesty, or that I am just pretending that I am putting myself down to get a compliment in return, like: “Of course you do, you draw really well…”

I can draw, and I draw well. But I do not think it comes from a gifted talent. I even think that the way we perceive the notion of having a “gift” for something as a necessary condition for creativity to bloom and be in service of any sort is problematic (or the load of similar connotation such as “innate talent”, “genius”, “prodigy” for that matter).

The “gifted” box trap

The distinction between the “gifted” and the “ungifted”

To begin with, “being gifted” with something is a difficult concept to define. There is no certificate that confirms whether a person is innately talented or not. Yet, this has never stopped us from separating the “gifted” from the “ungifted” from a very early age.

The danger of this practice of distinction is that it falls on the adults to decide whether a child has the right to continue to create. We tend to think pragmatically that if a child is not gifted in a field from the beginning, there is no point in guiding him in that direction. He or she is unlikely to succeed anyway, especially while being in comparison with those who have been identified as talented. This is also one of the arguments that lead some parents to stop their children from following an artistic path altogether. In this case, the wish of the child is considered utopian compared to his or her “real” potential.

As for the adults, in this era where we are constantly looking for a quick and easy solution, the “gift” can very quickly become an excuse not to start to take on something (despite the desire that has been going on for years), or to amplify a lack of self-confidence.

With such reasoning, this concept of a gift (or lack of it) for something could be very misleading, suggesting this kind of tendency to assume that the life of the “gifted” is easy, that they will be showered with success and fulfilment no matter what they do with their time.

Some children with gifted talent are forced to practice and create at all costs for fear of wasting their rare gift. On their shoulders carry the heavy load of pressure to succeed. And yet, there are obviously those who have innate talent in a certain field but have no desire to turn it into a career whatsoever.

At the other side, when it comes to people who decide to pursue and develop their innate talent, they face a common misconception that is unfortunately all too common:

“Being gifted” equals “having it easy”

You may find this odd, but most creators (including myself) are not that flattered when others complement our “God-sent gifts”. It gives us the impression that others think that all the success of our work is based on luck, that our efforts and years of practice are negligible, and that creating is just as easy as snapping fingers.

Though, until few years ago, my opinion was completely different. As one of the children who was classified as “ungifted”, I thought for a long time that in order to be legitimate to create, I had to show that I had a God-sent kind of genius talent. And as such, I was convinced that if I could show that I was able to achieve perfection effortlessly, others would believe that I had such a gifted talent.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and Stanford University called this phenomenon the “duck syndrome”. They discovered this syndrome in students who strive to give the impression that they have everything going for them. These students, like a duck, appear calm and placid on a superficial level, but wade frantically to “stay above water” so they could meet with the academic, social, and social pressure of being at the top of their game.

To maintain such a performance without being able to let out the difficulties that they are suffering from is like carrying a lie that gradually damages their quality of life as well as their physical and mental health. Even though this point is a well-known fact by now, since society’s perception still associates “being gifted” with “easiness”, it is not tomorrow that the “duck syndrome” will stop spreading.

Should we disregard the gift?

If the concept of gifted talent is so problematic, would it be better if we got rid of it and value intense practice more as an ultimate means to success?

According to the 10,000-hours rule, discovered and published by Anders Ericsson, it takes about 10,000 hours of practice to master a given field. If such rule is accurate, do we all have as much talent as each other, and we just need to take our time and work hard?

The existence of child prodigies

Suppose we engage in intense practice in the field of music for 8 hours a day, 5 days a week for all 52 weeks of the year, it will take us almost 4 years to reach the 10,000 hours of practice.

Meanwhile Mozart was able to play a sonata at the age of four and compose his first concert at six.

There are prodigies whose talent is awakened at an early age without going through intense learning. The 10,000-hour rule does not apply to these children. Several studies have been conducted to try to solve the mystery of intellectual precocity in these children by analyzing neurobiological or socio-familial factors. And the results coming from those studies only accentuate one reality: unfortunately, not all of us are equal when it comes to talent.

Undoubtedly, the children with extraordinary talent like Mozart’s remain exceptional. And it does not prevent some thousands of people among us from becoming great musicians.

Predisposition

We cannot deny the existence of the “gift” in some individuals. However, this does not mean that those who are not “gifted” are not special. Many of us may have another kind of resources, knowing as a predisposition in a particular area.

In my case, I do not think that I have any innate talent in visual art, but I think I have a specific predisposition in colour matching. That does not mean that I could recommend for sure exactly what colour you should use in your PowerPoint presentation or on your dining room wall. In my case, the predisposition manifests itself in the fact that I have never been blocked in the choice of colours in my illustrations, without having any specific explanation behind it.

Absolute pitch, or the ability to identify a note played in isolation, is another example of predisposition. Having an absolute pitch does not mean having talent in music. Although the concept sounds fascinating, this feature of ability is not that rare. Absolute pitch is most often found in people who are blind from birth or became blind at a very young age. Inhabitants of countries with a tonal language are more likely to have absolute pitch as well.

Predisposition seems less extraordinary than the kind of gifted talent for genius like Mozart. Moreover, predisposition, which looks like a slight facility in a subfield, does not necessarily have any influence on professional success nor career development.

Two illustrators who have the same style and the same environment can have different predispositions. One may have an aptitude for perspective and the other for inking. This does not prevent them from acquiring the technical skills and knowledge in the element which is not predisposed to them (inking for the first artist or perspective for the second), and to find themselves in the end at the same level.

In the world of music, only 15% of musicians have absolute pitch, as indicated by a Californian study conducted in 1998 among more than 600 musicians.

Any talent can be acquired!

While trying to figure out a direction to take for my professional path, I had the opportunity to get in touch with several creators, some of them have been awarded with prizes in prestigious competitions and festivals. When I mentioned the subject of the “gift” in creativity, all of them would tell me the same thing: A gesture that seems so simple, so natural, so quick, and oftentimes considered as the proof of an extraordinary gift of the artist by the public, is actually time and time again the result of somewhere as close to 10 years of learning and practice, starting with ordinary and humble mini-gestures.

Practice will always be the key

The article The effectiveness of creativity training: A quantitative review states that training can increase creativity on all experienced subjects, regardless of the environment and the criteria.

We may think that a job as a “nez“, the kind of job reserved to people who are able to smell and design compositions of scent, certainly requires an innate talent. But François Demachy, a nez at Dior since 2006 and a perfumer for three decades, once gave insight about his job as following: “You have to ‘know how to smell’, it is an effort. Almost everyone is capable of smelling, but it is a matter of training.”

If you have found your passion and predisposition in the same area, you can start with that foundation and then keep practicing to reinforce them and leverage them as your strengths.

But what if you think you have no predisposition?

Let’s do some tests!

I discovered my predisposition for colour matching quite late.

At first, I did not like colouring. During art classes in elementary school, I was never good at colouring (colouring without going over the lines, making gradients…). So I thought that I was bad at colouring.

When I was a teenager, with the trend of drawing mangas, I stayed for a long time within the field of black and white drawing, until I was 25, when I discovered watercolour. As I immediately liked this new medium, I drew much more in colour, and by discussing with other watercolourists, I finally discovered that I am quite at ease with choosing colours. I realized that I had put myself in the “no colour” box, when the truth was just the soft pastel colouring technique that I was taught to use in elementary school did not suit me.

In the book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, Carol S. Dweck identified two types of mindsets: the growth mindset and the fixed mindset.

People with a fixed mindset are afraid of taking risks, they focus too much on the problem and not enough on the solution. On top of that, this society that we are living within encourages us to believe in some sorts of standards for intelligence or success that, for the fixed mindset, this all will eventually become sources of frustration, such as there is no point in following the creative path unless you have a gift for it.

People with a growth mindset believe that mistakes are a source of learning. They may feel bad about failure for a while but then would focus again on the solution. These people do not lock themselves into the “gifted” or “ungifted” box and are always willing to explore new possibilities.

The best way to discover your predisposition, and even your talent, is to keep a growing mindset.

Above are few pragmatic observations that I have learned on my journey to becoming a professional illustrator. But if I have to make a conclusion on the subject of talent in creativity, I will say:

Forget about talent!

The problem with “innate talent” is not in the concept itself, but in how we interpret it.

Presented to the question, “Of course we can all create art in some forms, but only a few of us can be great, can’t we?”, Elizabeth Gilbert made an answer in her book “Like magic (Big magic)” as following:

“…I beg you not to worry about such definitions and distinctions, then, okay? It will only weight you down and trouble your mind, and we need you to stay as light and unburdened as possible in order to keep you creating. Whether you think you’re brilliant or you think you’re a loser, just make whatever you need to make and toss it out there. Let other people pigeonhole you however they need to. And pigeonhole you they shall, because that’s what people like to do. Actually, pigeonholing is something people need to do in order to feel that they have set the chaos of existence into some kind of reassuring order.”

These lines were liberating for me. They allowed me to start this very blog, me who is not good at expressing myself, me who found no predisposition in writing.

Not every creative hobby has to turn into a career. As long as you enjoy the act of creating itself, then the concept of being “gifted” should not stand in your way of having fun.

Few ending words…

I do not have any gift for drawing.

But when I encounter an Art director that I want to collaborate with, I will still say that I am motivated and that I am confident in our collaboration, despite not having any gift for drawing. I know the skills that I have acquired and mastered through years of practice, and I am aware of the importance of continuous learning, and so there I am, striving every day.

Most importantly, I have fun every day doing it!

In every child there is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist as you grow up!

Pablo Picasso

Keep creating!

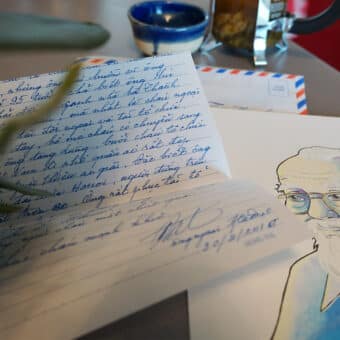

Tu Ha An

*Please consult the information on Copyright & Intellectual Property before copying or mentioning the content and images of tuhaan.com