The french version of this article is written in collaboration with Jo, my editor-in-chief. Edited by my beloved friend K.L

Following the interviews of six illustrators for the special series “Illustrator: the profession“, and through the discussions that I had with some readers of my blog, I noticed that many artists hesitate, or even forbid themselves, to take inspiration from cultural elements. They are afraid to fall into the trap of cultural appropriation, or to offend people coming from that culture, in ways that they have no way to control nor predict.

To solve this concern, or at least to get a hint of what could be done about it, I find it would be most helpful to talk to a representative of the publishing industry, and of illustrated book in particular, to get their point of view on this innegligible issue.

Recently, I discovered Élan vert publishing house while walking around the basement of a popular bookstore, looking for a gift for my godson. He is the second-generation Vietnamese, born and raised in France. I wanted to find him a book that would allow him to be comfortable with his difference in origin and physical appearance compared to his future schoolmates.

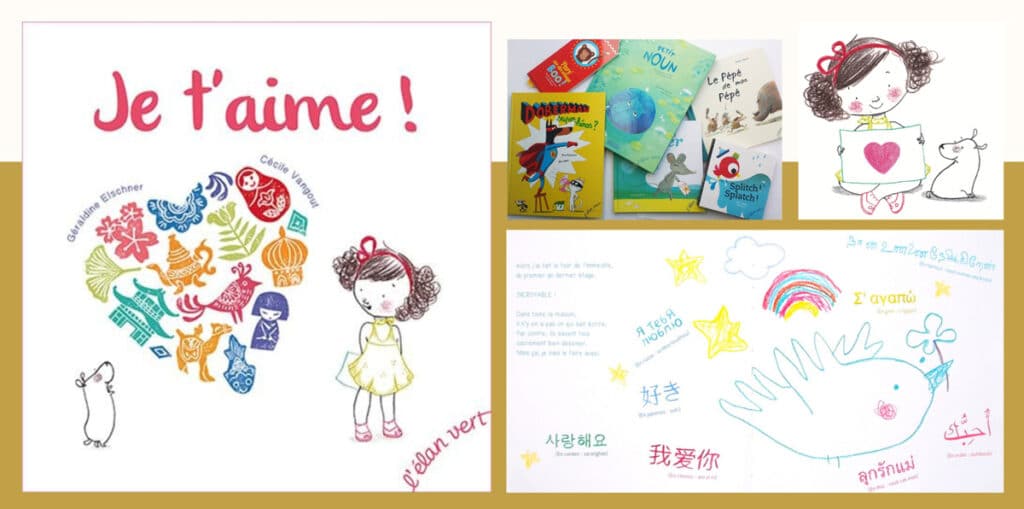

At that moment, I came across Je t’aime!, a book published by l’Élan vert. This book is a story of a little girl who asks the neighbors to write “I love you!” on her drawing and discovers many different ways to express love in different languages. This story is filled with cuteness, and their approach to representing cultural difference is so clever.

For this first interview of the year 2023, I had the honor to talk with Chloé Laborde, editor at l’Élan vert, about this very subject of cultural appropriation.

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, in this interview, you will discover the subject of the representation of diversity in children’s books, in a relaxed atmosphere, full of cheerfulness. You will also discover the behind-the-scenes of children’s publishing. And moreover, this article is also a goldmine of information and advice for illustrators who wish to work in the world of children’s literature.

Table of contents

Here is the table of contents, to facilitate your reading, rereading, and future research:

L’Élan vert – the impulse to become open-minded

The Origins of l’Élan vert

Tu Ha An (An): The first question, just out of curiosity: Why did you choose the name “L’Élan Vert” for the publishing house?

Chloé Laborde (Chloé): L’Élan Vert was created in 1998 by Jean-René Gombert and Amélie Léveillé. Prior to that, both of them already had experience in publishing. Jean-René created a publishing house in Canada called Études Vivantes, and he wanted to use the initials, so E and V.

Initially, L’Élan Vert was much more about documentary. Within our publishing house, there has always been this desire to be close to the environment, to work in harmony with the nature that surrounds us. There was also this play on words for the impulse to read, “l’élan”, to imagine. So it all was just right!

At the beginning, we made a lot of purchases of publishing rights. At the time, we were packager. In publishing, packaging means proposing projects to other publishing houses. Not all publishing houses have in-house editors, they outsource a lot. We worked for other publishing houses, like Bilboquet, or Vilo jeunesse… We built the editorial programs, and they would be then published under their brand. These publishing houses paid the authors and illustrators, while we searched for projects for them.

From 2007, we were able to develop our own catalogue.

The drive for cultural diversity

An: Did L’Élan Vert aim to topics embrace openness and diversity as its running theme since 1998, or did it start later in 2007?

Chloé: I joined L’Élan Vert adventure in 2007, at the same time when L’Élan Vert began to develop its current catalogue. To be honest, I’m not sure.

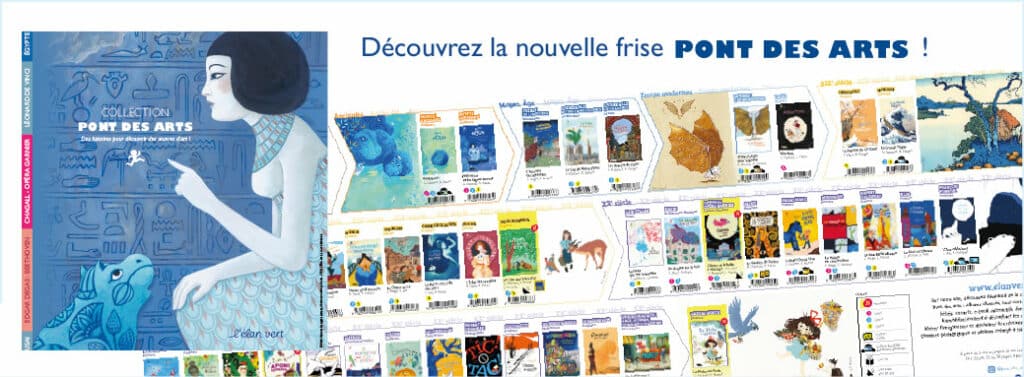

We first developed a collection about the environment, then we made our Pont des Arts collection, which was about introducing Art to children. And when it comes to Art, it’s inevitable to talk about cultural diversity.

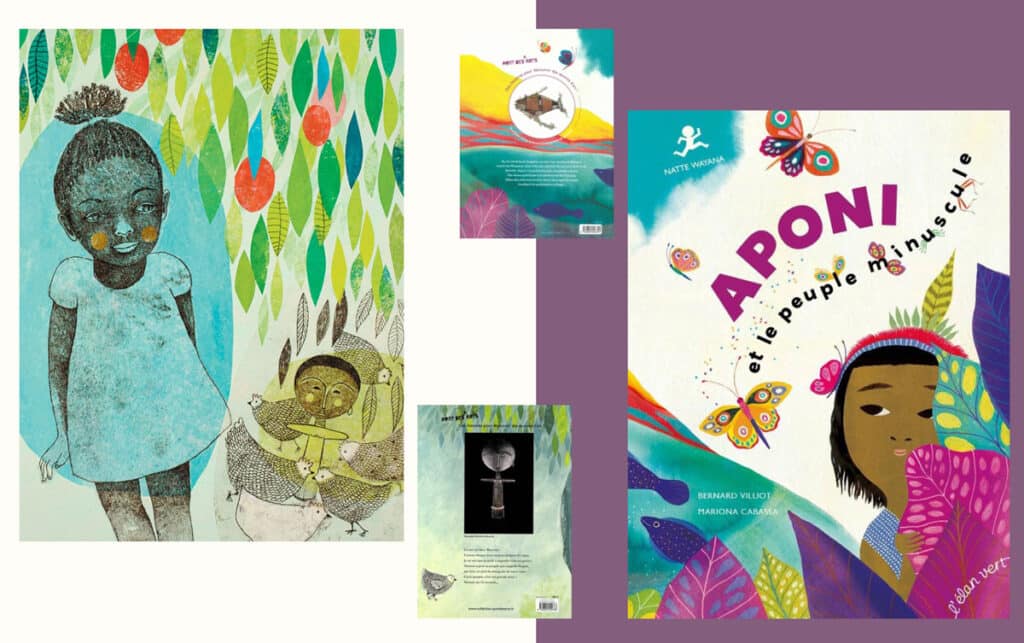

It has always been a pleasure for us to work with international artists, or to highlight the beauty and the value of things that from other cultures. We worked on AKUA-Ba doll for the theme of maternity, and Wayana mat, in Guyana, to talk about an initiation rite of passage from childhood to adolescence.

We always love working on the tales worldwide. When we were packagers for Vilo jeunesse, we were in charge of editing a collection of tales. There were thematic tales, but also tales from different countries: tales from Vietnam, tales from Russia… We always wanted to go beyond the Western world.

L’Élan vert, universes builder

An: I have another question out of curiosity as well. I live in Dijon, and I saw that you have a book called L’Ours Pompon et la baleine Gobe-Tout. Is the white bear the bear that was created by François Pompon, which is now in Dijon town center?

Chloé: Yes, the bear is in the Musée d’Orsay, and this is our reference art work for our collection!

Initially, it is an art bridge called L’Ours et la Lune. This album became very popular, and we made another album in square format which is L’Ours Pompon et la baleine Gobe-Tout, which spoke about the plastic pollution in our oceans. There was also an all-cardboard one destined for babies. These titles are now out of stock, but we don’t exclude the option of running another reprint for them.

Oh and we even made a plush toy as goodies as well. The plush of Pompon bear! And, my oh my, it is so soft! *laughs* It’s pretty cute, and by the end, it seems to be sensible thing to match the album and the plush together.

Conveying the beauty of diversity through our “coups de coeur”

“We want all children to recognize themselves in books”

An: I am happy to see that today there are increasingly more contents that embrace cultural diversity, gender diversity, or body diversity…

But on the other side, I also think it is unfortunate that the criticism coming out of the woke movement and cancel culture can make illustrators and creators, especially those who work towards the grand public, become more reluctant to take inspiration from other cultures for their work.

From a publisher’s point of view, especially when your direction goes towards culture diversity, did you experience these hesitations?

Chloé: We didn’t have so much hesitation, our focus is on our album.

I know that in Germany there was a big problem around Native Americans. Nowadays it seems that it is particularly hard to attempt telling stories about Native Americans as a non-Native Americans, because so far many stories were written based on a colonialist and fantasy point of view and it is strangely believed that anyone trying to do so afterwards is doomed to follow the same path. I think we have less restrictions of this type in France.

So far, as publishing house, we released many tales of the world, we did the best we could, and don’t think we are illegitimate.

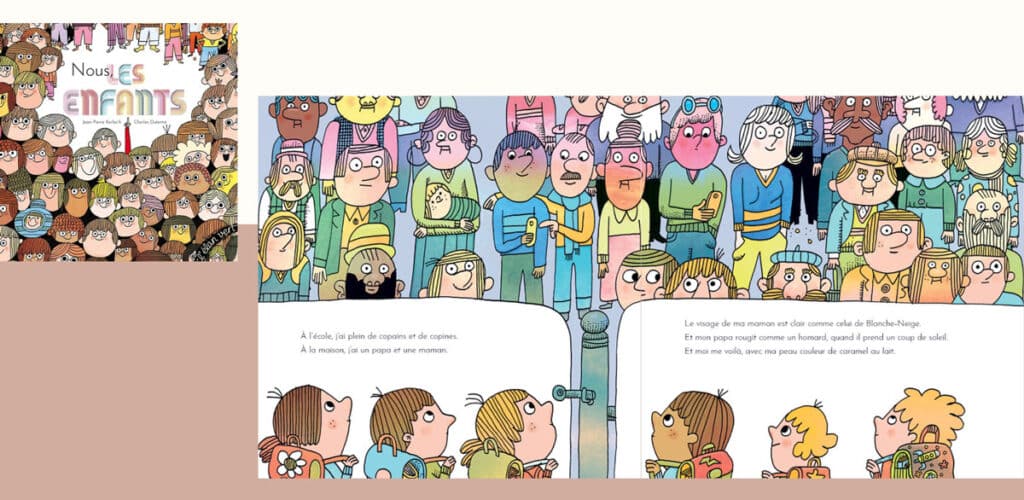

On the other hand, we try to show life with the reality of everyday life. We want all kids to recognize themselves in the books they read, so we don’t have any hesitation to include kids of any background, any hair or skin color, and any body type.

Actually, it’s harder for the morphologies, because oftentimes illustrators tend to draw characters perfectly aligned with what is considered the “norm”, while we prefer showing that the world is plural.

As a matter of fact, we practice this approach even more often in books where diversity is not the main theme. We just want to naturally show that being diverse is how the way the world is.

And we try to be open as much as possible. We do not have books that come too forward about a certain subject just for the sake of making a stand about it. In one of our books, Nous, les enfants, there is a school outing scene where we present two dads waiting for their children together with no written narrative nor any sign of affection between them. We let our reader have the freedom to interpret in ways they are most comfortable with.

About the questions of identity, we haven’t found yet a story that could make us want to produce an album. We will soon have a novel on the subject, but not yet any album.

We are not in it for the long haul because this is not our style. L’Élan vert is not a militant publisher like Talents Hauts, La Ville Brûle, or Rue du monde. These publishers are very committed to open their audience to reading, to diversity… Our goal is to make children dream.

An: I think that, of course, we need militant books. They give strength to those who need it and who want to carry, claim, or transmit these values. These books remain sources of information to make constructive discussion with people around us.

However, I find that this approach might only be able to convince people who already agree with the content

With a more easy-going approach like yours, which makes people dream, with a lot of humor as well, we can tackle subjects that, perhaps, parents of children have never heard of. We can also introduce a child to a relatively more complex subject that carries more depth.

Surface inclusivity and the children’s literature approach

An: I feel like today, in communication materials, to make sure that no racism can be deduced by any chance, there is a tendency to include in mass a white person, a black person, an Arab person, an Asian person… Such tendency can be easily spotted in the catalogues, the advertising or communication campaigns of various brands and companies.

As an anecdote, there were times when my photo was chosen for communication supports only to fill a quota.

Chloé: It must have been weird… Even if I prefer that there is a diversity in magazines, it is true that, sometimes, the execution of this ideology is pushed to the extreme.

Nevertheless, I don’t think the public could be easily fooled with superficial setup, namely by filling up the quota as you said. What has been done is unarguably a great effort. But in reality, racism runs deeper and is more than often unobservable. Needless to say, we still have rooms for improvement.

In children’s literature, we, as publishing house, don’t stress about the origins of the authors to judge their legitimacy to write about a subject. It’s not because we are running a story about Mauritius that the authors need to be Mauritian. We trust our illustrators to do proper research. Maybe we will make mistakes along the way, but there is the documentation, the graphic style, and the freedom for our readers to embrace the fiction part of our creation.

The representation of Africa in literature can be a very interesting case to illustrate this point. We see very often that in books, when it comes to Africa, the images of the savannah, the huts will be omnipresent. And there is this illustrator, named Alexandra Huard, who, precisely, wanted to break these clichés and show Africa today with its colorful cities.

We also published a book entitled Binti la bavarde, about a little girl who lives in Mayotte. This album is the result of years of living there of their authors, Véronique Massenot and Sébastien Chebret. They set up their project there, and they integrated a lot of hints from the life that they observed. In the book, we find reproductions of street art that can be found in Mayotte and can almost live the real spirit of the cities with, the markets, the cabs, the fabrics … This book is truly at the edges of the documentary sector.

Unfortunately, when you do a book about a country, you cannot always have the authors living there just for the sake of the project. And that’s too bad! *laughs*

Our ultimate compass is desire

Chloé: The readers should have the complete right to choose to read, or not to read a book, if they feel that it is not representative enough.

Eventually I don’t want to make mistakes, but I wouldn’t stop someone to create a piece about Vietnam just because they are not born Vietnamese. We can never please everyone, but putting people in these little boxes based on their origins is not a way to go. Also, in the end, it is very much up to the public to find their way to receive what’s created.

We published a Chinese tale called Nian Shou. Therein, we made the decision to stay with traditional costumes since it is an ancient story. But it would be absurd to think that such decision of ours means that we don’t know that China of today does not look anything like the representation that we went for. When we work with tales, such as Little Red Riding Hood and Thumbelina, we wouldn’t dress the characters the way children of today would dress themselves, with sneakers and H&M clothes. Our job is to create a world of stories that can make people want to dream, instead of sticking with the reality just for the sake of being appropriate.

At l’Élan Vert, we just don’t like the ultra-realism.

When we work on Egypt, we focus more on Ancient Egypt than on present-day Egypt, because it has so much potential for dreams. We want to be in the time of pyramids builders, and not in 2023.

For our works, we choose the moment that is going to bring more to the dream rather than pondering too much whether we are offending someone.

An: It seems to me that when you want to publish an album, you make decision based on your desire, and not on the fear of upsetting a person or a group of people?

Chloé: Yes, we are a publishing house of “coups de coeur”. We do run commissions on collections that aim to introduce arts. But we produce our albums only because we have a crush on the texts that we received. There must be a real enthusiasm at the beginning of the projects.

The editor and illustrator VS negative feedback

Always start with the goal

An: Have you ever had negative feedback on your books, especially on the ones about controversial subjects?

Chloé: We don’t work a lot on controversial topics so we don’t necessarily have negative feedback on them neither. We have never been attacked for publishing tales of the world. We just ask people, mostly French, to give them a try.

However, we were criticized for our Pont des Arts collection.

In the albums of this collection, we completely took over a piece of art and told a new story about it. In a way, we broke down the work. Some people were bothered because from their point of view, we shouldn’t take the painting out of a context in which it was created and do whatever we want with it.

But we are making conversations with children. We want them to discover the artist’s universe and to form a real encounter with the work. It’s not interactive if we just parade through a museum. But if there is a story behind it, we can create a real exchange between the child and the piece of art, which will eventually become a part of the child. And when it comes to Mondrian, Picasso, Matisse or other very recognizable styles, if the child can associate the work with a style, they will be able to recognize a Picasso the next time they see it.

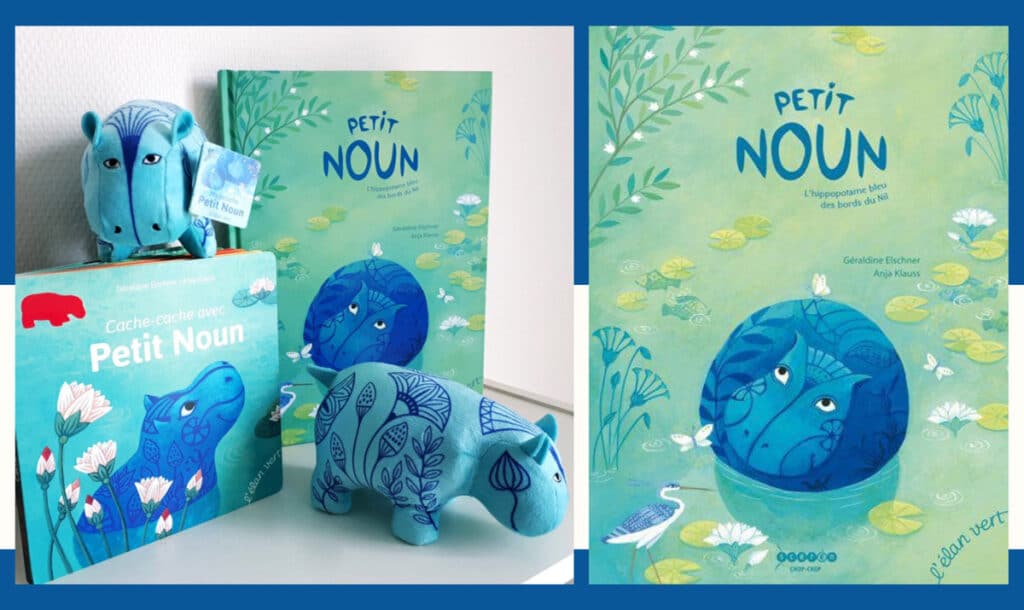

There was a real craze around our Petit Noun, a small blue hippopotamus from ancient Egypt. Initially, all the amateurs of Egyptian departments knew this little blue hippopotamus. There are many specimens and they exist in all the Egyptology departments of the world. But in France now, children know it too, and call it Petit Noun. Even the Louvre museum calls this work Petit Noun, even though it only came out of the author’s imagination! And that’s great, this approach has really given a name to a work!

We received bad reviews as well as enthusiastic feedbacks. Pont des arts is a collection that has been suported by the National Education, by Canopé, for an exceedingly long time. The teachers have been picking it up as well, and I think that is great.

The only sharp criticism that we had was on a work whose story that took place during the First World War. We got criticism like, “No, that can’t be, because in 1916, there wasn’t such and such a weapon, yet it’s represented in your book!” Certainly, it is interesting for people who know about the First World War. But we don’t think that this fine accuracy is that crucial for child who is approaching a different story in that book. That’s not really what the book is about.

Tomatoes or roses, the choice is ours

An: Nowadays, many authors or illustrators, me included, are very visible on social networks. Since it’s so easy to be in contact with fellow creative people on these networks, the public is more open to give their opinion and we often get direct feedback in comments or private messages.

Do you have any advice for creators who wish to exhibit their works that represent diversity, knowing that it is a subject that attracts criticism?

Chloé: I hope artists could trust themselves. Social networks can be double-edged.

When you are an artist and you publish your art work, it means that you like it, that you want to share it, to defend it rather than to receive tomatoes. My suggestion for the creators is to leave the tomatoes behind, and pick up only the roses instead. You can choose what you read. Even protecting yourself and choosing not to read is not a forbidden way neither.

Besides, I have the impression that unconstructive comments often come from the ones who think the least. It’s important to take a step back.

Getting noticed by a publisher: tips from an editor

Instagram is still a great tool

Chloé: Despite the drawbacks and controversies, being on social media is still a great way to get noticed as an artist. When we’re looking for new illustrators, we, as the editorial team at l’Élan Vert, often go on Instagram. I know a lot of Art Directors do the same thing. In that sense, Instagram is a real tool for illustrators.

After, you need to know your dosing, and alternating social networks like Instagram with other types of marketing is to be recommended. For example, don’t hesitate to send your portfolio by email to publishing houses. Don’t hesitate to follow what the different publishing houses are doing neither. This will allow you to see what publishers are looking for and how your style can fit in with their publications…

An: Thank you very much for these tips. Precisely, “How do I contact publishing houses?” is the question I often get from young illustrators who follow me on Instagram. And these are questions I’ve asked myself as well.

My guess is you have been receiving a lot of portfolios from illustrators?

Chloé: Yes, we do. And yet, we are just one small independent publisher. I cannot even imagine what Gallimard or Flammarion must have been receiving.

Despite that fact, it is still necessary to reach out by sending in your portfolios. If you don’t send anything in, we cannot know you. At the same time, keeping your Instagram alive to show who you are can be a real plus towards editors at publishing houses.

For a successful prospecting email

An: Since you receive many portfolios from illustrators, do you have any advice for young illustrators so they could stand out from the crowd?

Chloé: I would tell illustrators to show both characters and backgrounds in which these characters would evolve. In the sector of children’s books, we, as publishers, need to pay attention to the backgrounds, we need a double page, and not only simple characters. We like to see how you can bring your characters to life, but also your capacity in terms of staging, your sensibility with colors…

And the best advice is to look at what the publisher is doing and ask yourself if your style fits the target publisher. Then, perhaps, depending on the publishing house’s editorial line, include one or two images in the e-mail to show your work, to “bait” out the publishing houses a little and show them your identity.

The future of children’s books

An: At the time of this interview, the paper shortage is a real crisis. Do you see it as a danger for the future of children’s books? And apart from the paper shortage, are there any specific problems that threaten the evolution of the sector?

Chloé: The paper shortage is indeed a problem, but it will not be a problem that would last forever.

What kept us in balance was the fact that we were printing in both Asia and Europe. We used to print in China, where paper supply is rather abundant, but recently transportation was greatly disrupted, so we focused on Europe. We now run 95% of our printing right here in Europe.

Thanks to the existing culture of children’s books in France, I don’t feel that the sector is in danger. We’re surrounded by a rather culturally rich environment, even teachers take a great interest in books for children. At school, they try to give children a love of reading.

If at one hand, there are many children who do not have the chance to have access to books and don’t even have a bookshelf at home, on the other hand, those who do have access to books, and who love books, are much likely to pass this love on to their children. Reading a paper book is a pleasant experience on its own. Taking out the tablet to read a book to your child is much less pleasant than being able to take the book object, to touch it, to turn the pages… There is something very cocooning because it is a pure moment of exchange. I am sure that my daughters, when they become mothers, if they want to, will want to share this with their children.

Perhaps gradually, there will be fewer people who would be interested in paper books. But those who like them often have an uncompromised bond with them. The books as objects that we know, and all the moments spent around it, will be passed on from generation to generation. For this reason, I am not particularly worried about the book as an object per se. I am convinced that paper books are irreplaceable, and we will manage to convince new readers of the joy of reading, of sharing a story.

As far as the publishing market in France is concerned, it is enormous. Thousands of books get published every year. There is much more supply than demand, so it is not easy to ensure a solid good foot. For all those who want to see the prospect of children’s books in French market, going to the Montreuil fair the first week of December is a must to fully realize to which extent creativity can go. There are so many beautiful and inspiring things out there every year that we are blown away everytime.

An: A friend told me that a children book is read three times: the first time by the parent who reads to the child; the second time by the child when they start to learn to read on their own and rediscovers the story by themselves; and the third time is when the child becomes a parent and passes on the children’s book to their child.

Chloé: Yes, that is true. There is always the pleasure of reading. Oftentimes, a child book is not usually read just once and then went forgotten. When a child book becomes a child’s favorite, the child knows it by heart. A child book is meant to be read, re-read, over and over again…

Some stories, often those that were not expected, bring a real enthusiasm to the child, a bit like the comforter: it is this story and not another one. And it is always a bit magical to see a child take hold of a book.

Trust yourself & Keep creating!

Tu Ha An

*The article by Mademoiselle Coralie: https://mademoiselle-coralie577.blogspot.com/2016/03/

*Please consult the information on Copyright & Intellectual Property before copying or mentioning the content and images of tuhaan.com